Travelling, Teaching and Training with Jeremy Loflin – BJJ Globetrotters

“I like to see how other people do things differently than the way I do them and see how other people think differently than the way I think.”

Jeremy Loflin

Name: Jeremy Loflin

Age: 44

Belt: Black under Paul Thomas Brazilian Jiu Jitsu

Profession: I own and run a window covering installation company. My second business is the Fight Lab in Katy, Texas. It’s a small Jiu Jitsu school.

How many years in BJJ: I’ve been in Jiu Jitsu since 2005.

Other martial arts: I’ve done no other martial arts except wrestling when I was a freshman in high school.

Where do you live: I live in Katy Texas that is just on the outskirts of Houston.

Where are you originally from: I’m originally from Houston but I grew up in Southern California and left there in 2005.

Fun fact: I was lucky enough to live next door to a girl in high school who I started dating married and we just celebrated our 20 year anniversary.

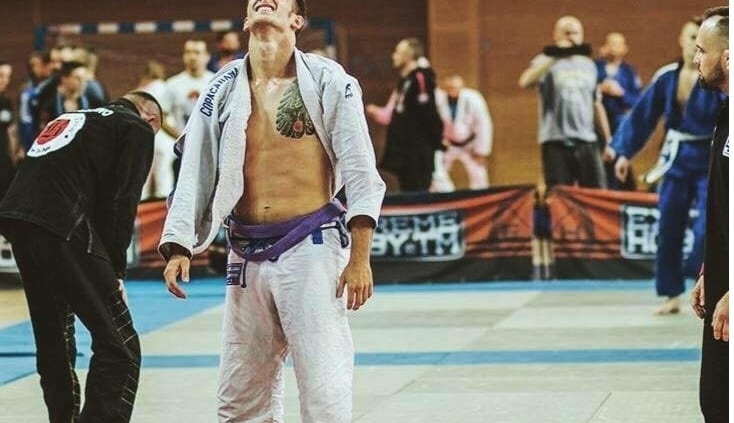

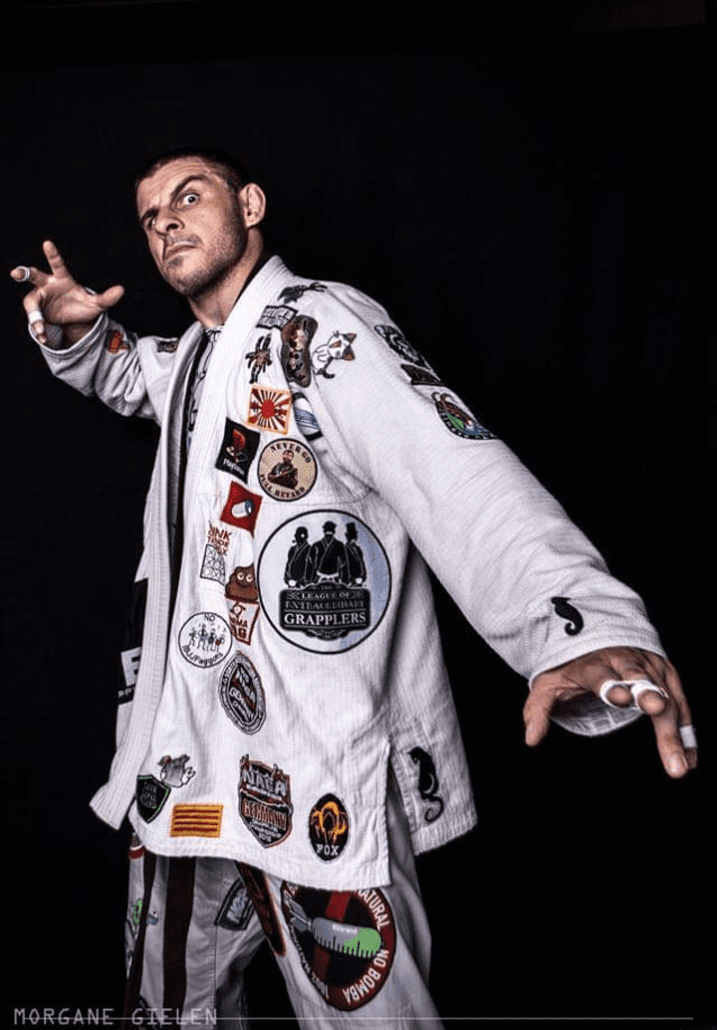

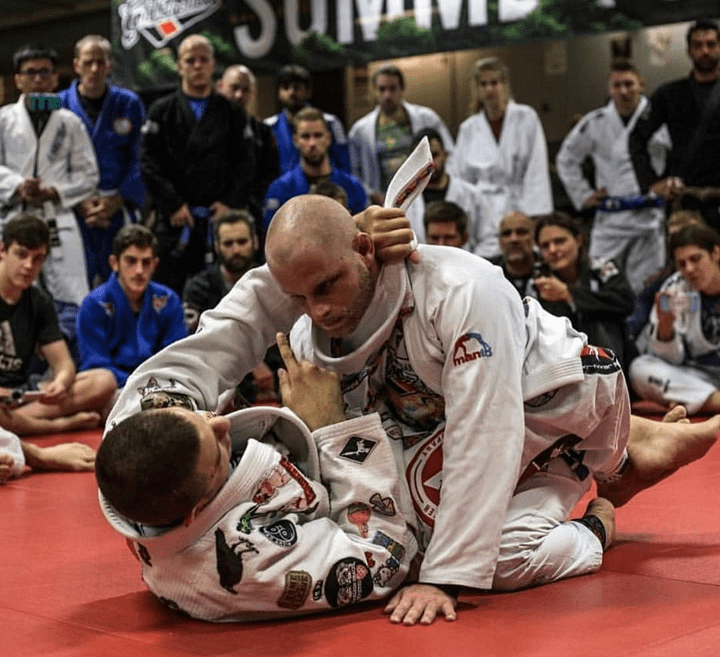

Jeremy Loflin BJJ Globetrotters

Tell us what inspired you to travel and train?

I like to see how the other half lives, whether it be how they live in their lives or how their gyms operate. I like to see how other people do things differently than the way I do them and see how other people think differently than the way I think. Hopefully I’ll learn something and maybe I can share something that keeps it fun.

Tell us about your most recent travel and your upcoming travel – where have you been and where are you going?

I’m going to Mexico for Christmas unfortunately I will not be training. I will be going to the Globetrotters Caribbean Island Camp to learn as much as I can in February. In January I will be cornering an MMA fighter in Louisiana and hopefully I will have an opportunity to go and train while I’m down there. In May I will be going to the Maine camp.

Jeremy Loflin BJJ Globetrotters

What are the things you enjoy about traveling?

I love seeing new destinations as much as possible. I personally like to cruise – I’ve been on 30 cruises. None of them were Jiu Jitsu cruises but while on ships I’ve been fortunate enough to find gyms that do BJJ and have some fun rolls.

Can you give us some examples of experiences you had that makes it worth traveling and training?

I was in Spain sitting outside of a gym that look like it had been closed down for years and I was starting to think I was given some bad information. Slowly people started showing up one by one – the place came to life and we rolled for hours. At the end of it all we all hung out and I caught a ride on the back of a moped to the hotel to meet my wife and share some of the stories.

Jeremy Loflin BJJ Globetrotters

What has so far been the most surprising experience for you when traveling?

Another great experience I’ve had was while working down south near the border of Mexico I was wanting to train real bad but no gyms were nearby. I drove an hour one way and found a gym where nobody spoke English except one kid. We rolled and I was invited back. I came back, we rolled some more and I started coaching every time I went down that way and sharing Jiu Jitsu.

The most fun part of that was the delayed response in jokes and the wave of smiles and expression as we understood each other through delayed translation. I still talk to those guys today my Spanish has not gotten any better but thank goodness their English has!

Are you a budget traveller – and if so how do you plan for a cheap trip?

Unfortunately I am not a budget traveller. I should be but I like to be comfortable. I usually rent my own car and get my own hotel – that way I can come and go as I please.

If you were to pass on travel advice to your fellow Globetrotters, what would it be?

Always have training gear with you and always be up for the unexpected opportunity to train!

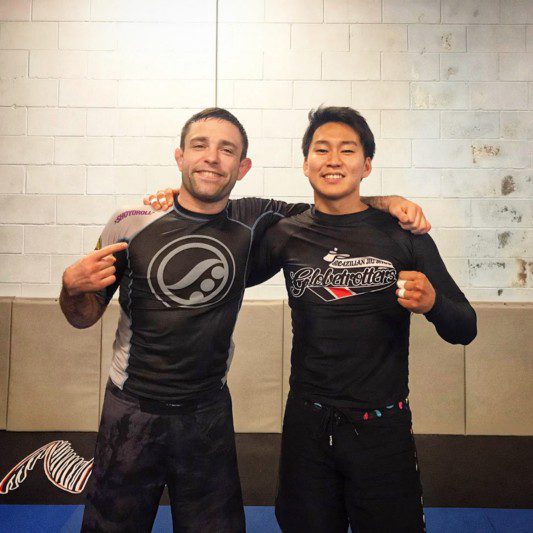

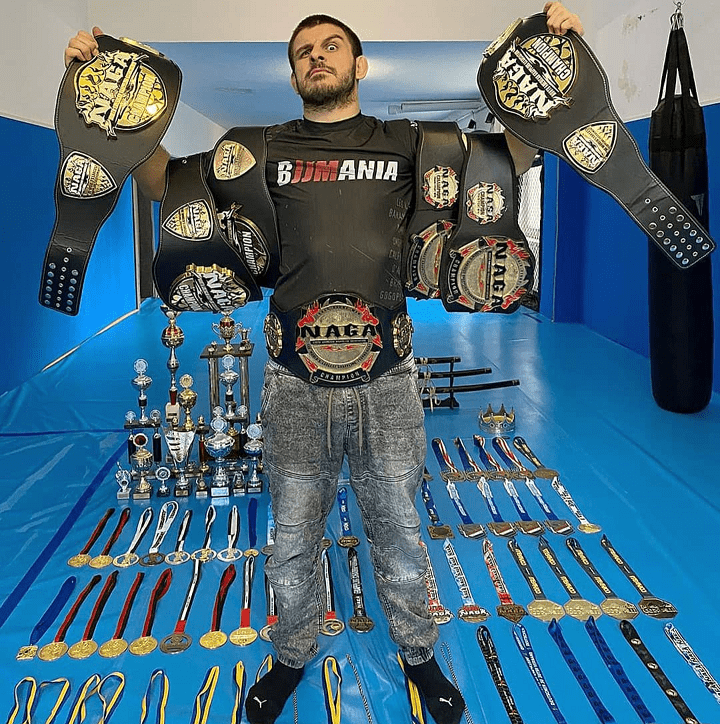

Tango DiNero BJJ

Tango DiNero BJJ